Last updated on October 1, 2025

Sudoku’s story is one of surprising invention, mathematical inspiration, and global curiosity. Although many think of Sudoku as a modern, quintessentially Japanese pastime, its roots actually stretch back centuries and span continents, blending European mathematics, American puzzle-making, and Japanese publishing into the icon we know today.

The Birth of a Puzzle: Latin Squares

The underlying principle behind Sudoku is the “Latin square,” a mathematical concept invented by the Swiss polymath Leonhard Euler in the 18th century. A Latin square is a grid where each symbol appears only once per row and per column—that basic logic is at the heart of every Sudoku puzzle. Euler’s idea was intended for mathematics, not entertainment, but it would plant the seed for future puzzles.

Early Number Puzzles in France and the USA

The idea of filling grids with numbers continued in the 19th century: French newspapers published puzzles akin to Sudoku, but with rules involving arithmetical sums and sometimes extra diagonal constraints. These never quite caught on as universal pastimes, but they provided a testing ground for logic-based puzzles.

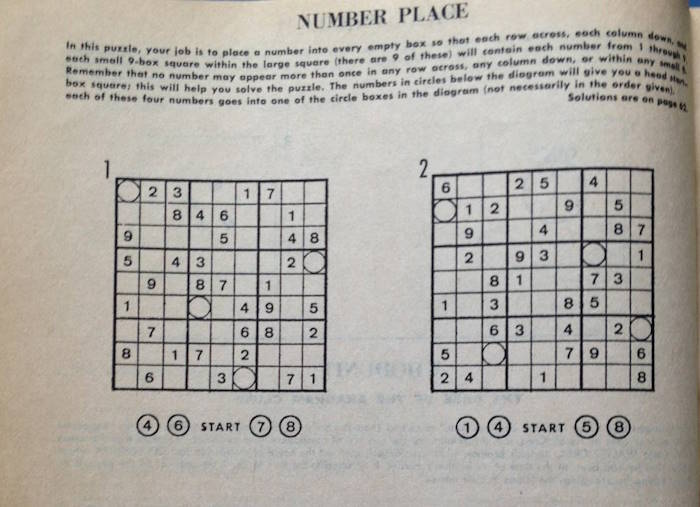

The crucial leap came in 1979 in the United States. Howard Garns (1905 – 1989), a retired architect in Indiana with a passion for puzzles, created what we now recognize as modern Sudoku. His puzzle, called Number Place, was first published in the May issue of the Dell Pencil Puzzles and Word Games magazine. Garns’s original innovation was a 9×9 grid subdivided into 3×3 squares, with the core rule that each digit from 1 to 9 can only appear once in each row, column, and block.

Although Garns name was nopt mentioned in the magazine, it was discovered that his name always appeared in the contributors at the front of the issues whre Number Place appeared, and was absent from all other issues2.

Sudoku’s Japanese Reinvention

How did Sudoku get its catchy, now world-famous name? In 1984, the Japanese publisher Nikoli discovered Garns’s Number Place and saw its immense potential. Maki Kaji, Nikoli’s president, introduced it in the magazine Monthly Nikolist under a lengthy title: “Sūji wa dokushin ni kagiru” (“the digits must be single” or “the digits are limited to one occurrence”)—quickly abbreviated to “Sudoku”.

Nikoli added important refinements: they capped the number of provided “givens” in a puzzle to 30, asked for symmetry in their placement, and standardized the minimalist “single solution” requirement. For decades, Sudoku was mostly a Japanese phenomenon, published in newspapers and devoured by commuters and logic enthusiasts.

The Global Sudoku Craze

The world’s introduction to Sudoku didn’t happen until 2004, when retired judge Wayne Gould of New Zealand stumbled across a Sudoku book in Tokyo and sensed its worldwide appeal. He wrote a computer program to generate puzzles and convinced The Times of London to publish Sudoku daily. The game’s simple rules, language-independence, and challenging play made it an instant international hit.

Within months, newspapers from the U.S. to Finland and Costa Rica were running Sudoku puzzles, and the game stormed onto the internet, into mobile phones, and onto bookshelves around the world. By 2006, there were already official world championships and endless variations—giant grids, “Killer” versions with arithmetic twists, even three-dimensional Sudoku cubes

Further reading

A very good recent article in French: https://www.stephanebataillon.com/sudoku-factory-20th-celebration-lhistoire-du-sudoku/

An old-fashioned website but with interesting information: http://sudokuuriq.50webs.com/History1.htm

Be First to Comment